Does Erythritol Increase the Risk of Heart Attack?

Does Erythritol Increase the Risk of Heart Attack?

Does erythritol increase the risk of a heart attack? A recent study has made its round in the news claiming it can. However, when we look at the study carefully, it may not be the case.

The study itself has a lot of limitations and problems. It is highly possible that a poor diet high in glucose and fructose was the culprit behind serum erythritol levels that may be correlated with cardiac events and not dietary erythritol. In this article, I want to take a detailed look at this study and the potential benefits and risks of this sweeting agent.

Erythritol and Heart Disease Study

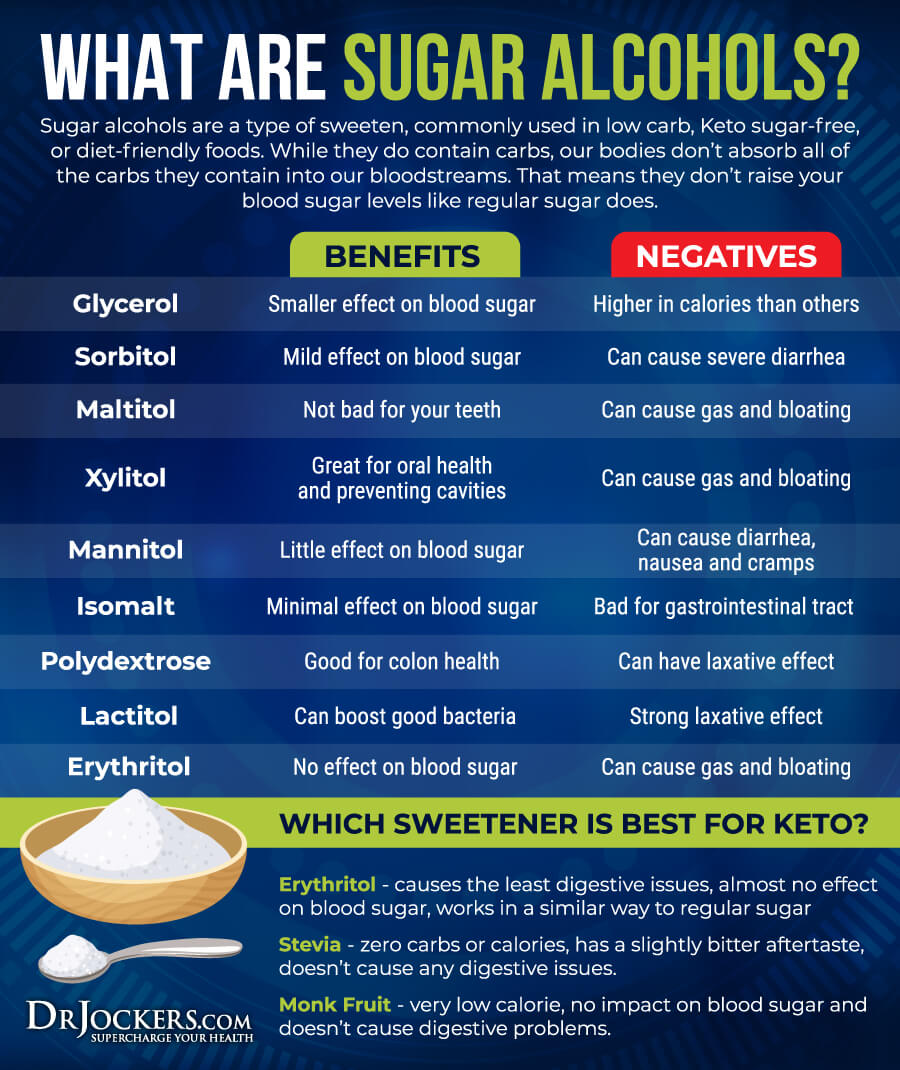

Erythritol is a type of sugar alcohol that’s commonly used as a low-calorie sweetener (1). It is made when a type of yeast ferments sugar (glucose) from wheat starch or corn in production facilities. It presents as powdery white crystals. It may be used as a helpful sugar replacement for those who are trying to limit their sugar intake or have diabetes, prediabetes, or insulin resistance.

There are other sugar alcohols besides erythritol that are used by food producers, including xylitol, sorbitol, and maltitol. These are low-calorie, sugar-free, or low-sugar sweetener products. Sugar alcohols are generally found in small amounts in nature, including in fruits and vegetables. Their sweet taste stimulates the sweet taste receptors of your tongue.

Erythritol is different from other sugar alcohols in a number of ways. It has fewer calories. Erythritol only has about 0.24 calories per gram. As a reference, xylitol has 2.4 calories per gram and table sugar has 4 calories per gram. Despite having about 6% of the calories of table sugar, erythritol is about 70% as sweet as sugar.

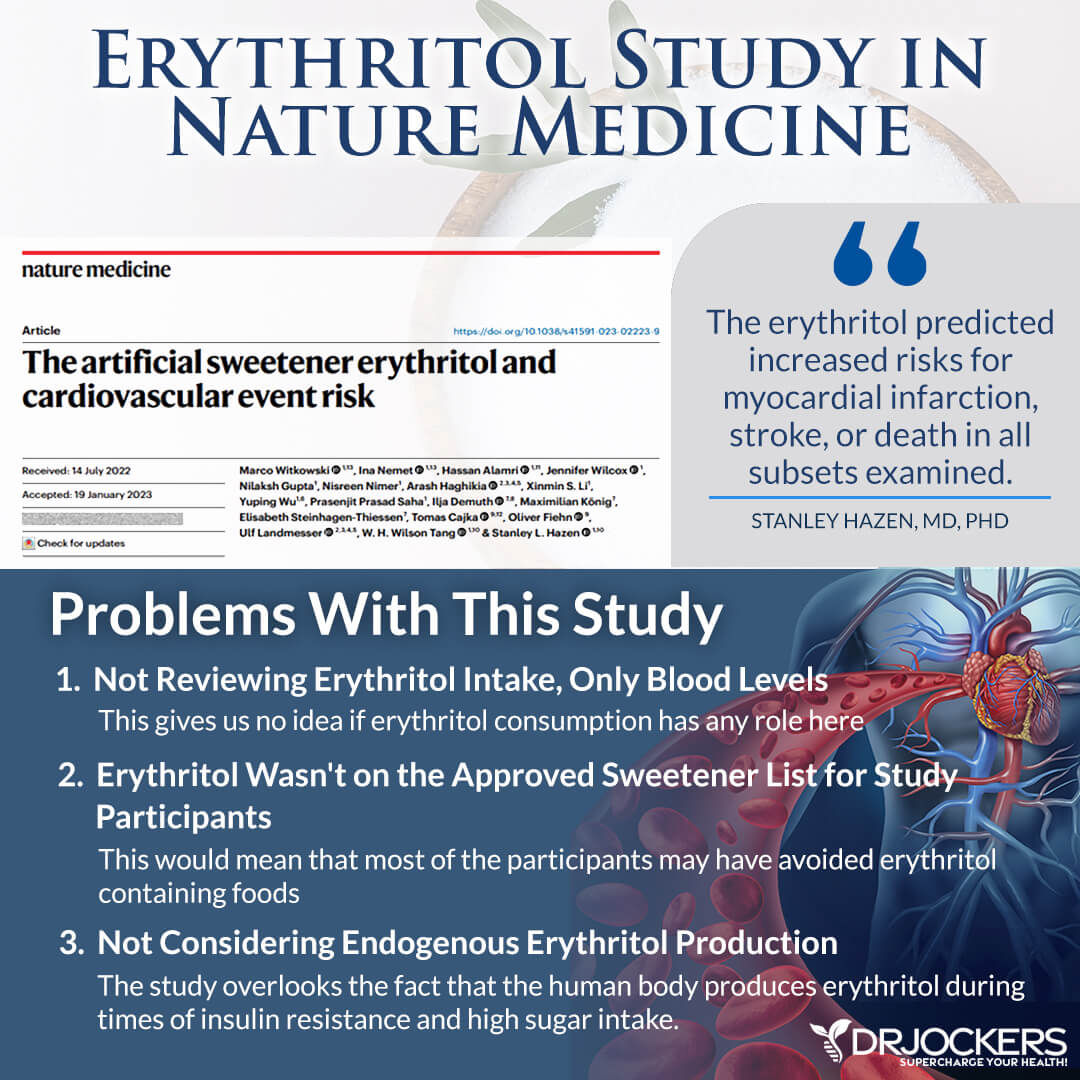

That sounds great, right? But is it healthy? Recent headlines have questioned this recently. According to a recent 2022 study published in Nature Medicine, erythritol may increase the risk of cardiovascular events (2). Scientists looked at erythritol levels in the blood. What they found was that people with higher serum erythritol levels had a higher risk of stroke, heart attack, and death.

Results of the Study

According to a CCN report on the study, “If your blood level of erythritol was in the top 25% compared to the bottom 25%, there was about a two-fold higher risk for heart attack and stroke. It’s on par with the strongest of cardiac risk factors, like diabetes. (3)”. The paper suggests that erythritol may increase the risk of blood clotting, which may increase the risk of cardiovascular issues, based on animal and limited lab research.

That doesn’t sound so good anymore. Don’t panic yet. Erythritol may not be as bad as this study and articles about it suggest.

There are three major issues when it comes to this study:

- The research didn’t look at the erythritol intake of participants, only the erythritol level in the blood.

- Erythritol is a marker of metabolic dysfunction and an overall unhealthy diet.

- We don’t know from the study if erythritol was simply associated with the increased risk of cardiovascular issues or caused it.

Before I go into detail and go over the problems with this study, I want to discuss how erythritol is a biomarker for metabolic dysfunction.

Erythritol is a Biomarker for Metabolic Dysfunction

The study didn’t look at the erythritol intake of participants, only their blood erythritol levels. It’s possible that dietary erythritol wasn’t the culprit behind high blood erythritol levels and potentially related cardiovascular issues (2). Why? Because erythritol itself may be a biomarker for metabolic dysfunction and a poor diet.

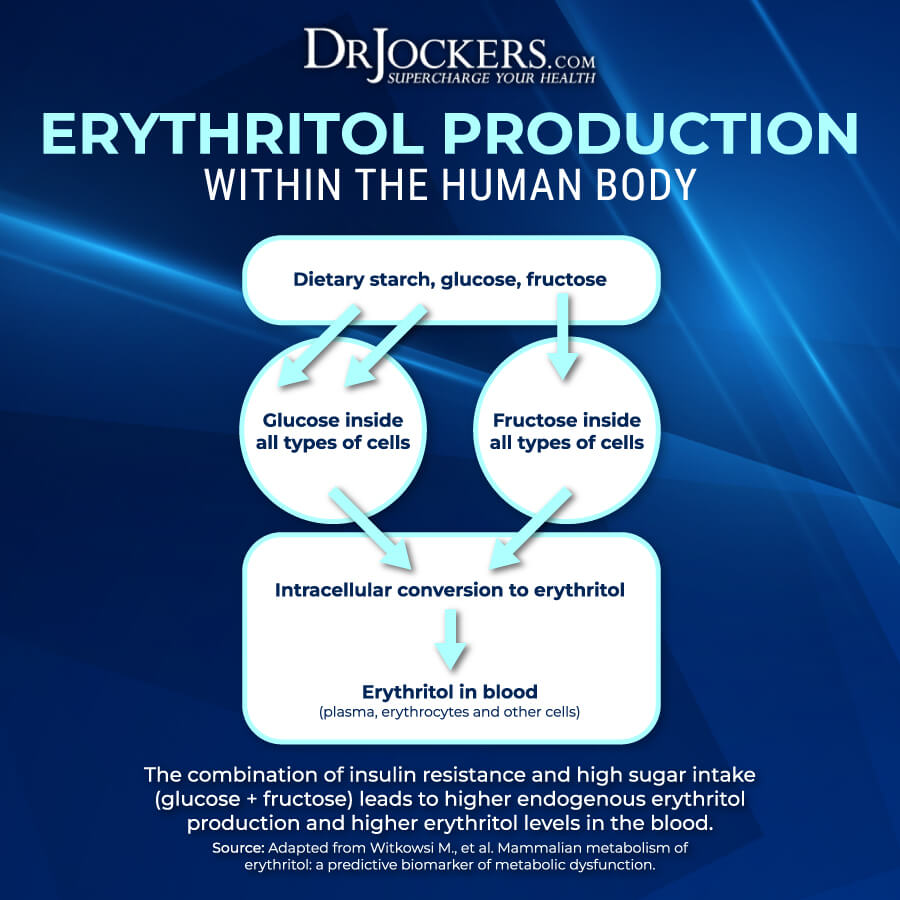

According to a 2017 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, the human body can make erythritol endogenously (4). This means that we can make erythritol inside of our own bodies.

This can happen as a response to the consumption of fructose or glucose via the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), which is a metabolic pathway parallel to glycolysis. According to a 2020 paper published by Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, the metabolism of erythritol may be a biomarker for metabolic dysfunction (5).

In the study published in Nature Medicine, erythritol was not widely available (2). On the other hand, the general population eats a lot of glucose and fructose-containing foods in the United States, Europe, and most of the Western world. It is very much possible, in fact, very likely, that the participants’ glucose and fructose intake was driving the increase in the level of serum erythritol, not dietary erythritol.

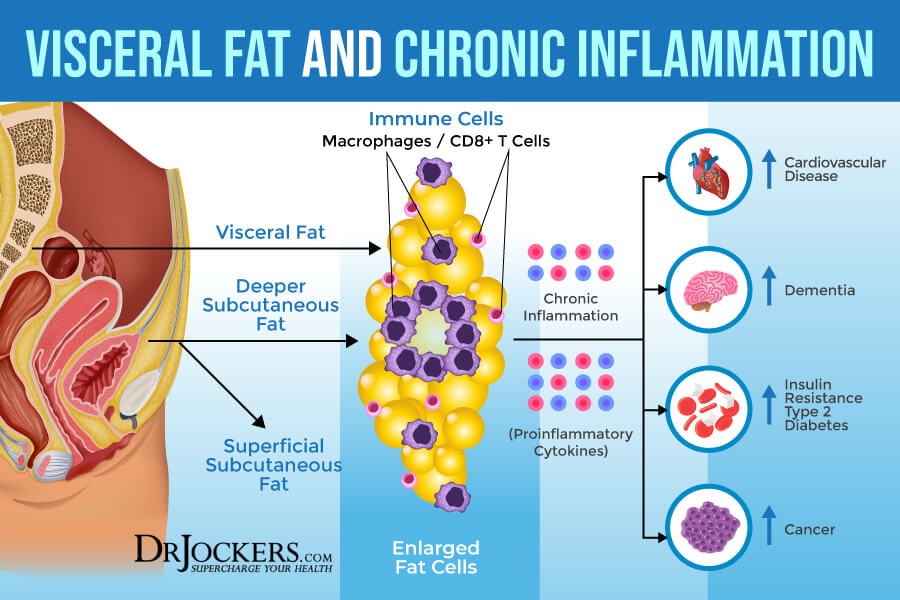

If this is the case, then the endogenous production of erythritol is what may lay behind the cardiometabolic disease. There is some evidence for this. A 2020 study published in Frontiers in Endocrinology has found that the PPP may modulate insulin sensitivity and increase obesity-induced inflammation (6).

A 2010 review published in Drug Development Research has also found a bi-directional link between PPP and high-blood sugar in animal studies (7). A 2021 review published in Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity has found that PPP can become dysregulated in people who are obese and have a metabolic disease (8).

In light of these studies, it seems that insulin resistance and high blood sugar levels combined with the overconsumption of glucose and fructose may lead to elevated serum erythritol levels. High levels of serum erythritol in the blood may be a sign of an unhealthy, inflammatory diet and metabolic dysfunction. This is important to understand as we discuss this recent study in Nature Medicine.

Problems with Erythritol Heart Disease Study

There are several problems with the this study and the headlines and reporting on the study. Let’s look at them.

Only Looking at the Erythritol Level in the Blood, Not Erythritol Intake

The research didn’t look at the erythritol intake of participants, only the erythritol level in the blood. As you already know, erythritol is a marker of metabolic dysfunction and an overall unhealthy diet. Knowing this may bring up some questions and call for follow-up research.

The study in Nature Medicine has found a correlation between serum levels of erythritol and cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks and death (2). In the media, journalists jumped on the study, claiming that consuming erythritol was the actual cause of increased blood erythritol levels. This may not be true since scientists didn’t measure the intake among the subjects.

Since we know that erythritol is a marker for metabolic dysfunction and may be a sign of a poor diet, it may be possible that consumption is not the issue, but a high-glucose, high-fructose poor diet is.

Erythritol Wasn’t on the Approved Sweetener List for Study

It’s important to note that erythritol wasn’t on the list of approved sweeteners when the study started. As the study progressed, it was still not widely used. This means that participants most likely didn’t have a high erythritol intake if any at all.

This study is not the only one that dealt with this issue. According to a 2023 review on erythritol published in Nature, other large studies that showed a potential link between serum erythritol levels and increased cardiovascular and metabolic risk had the same issue (9).

The two largest studies on the effects of erythritol were conducted before erythritol was approved as a dietary component by the US government. Since it wasn’t approved yet, the erythritol intake of participants was likely low on nonexistent, and dietary erythritol cannot explain the association between blood erythritol levels and cardiometabolic disease.

Moreover, in the studies that were done after the approval of erythritol and its introduction to our food supply, the level of erythritol consumption was still very low. In 2019, the estimated global per capita production was only 0.023 g/day. This likely didn’t support high enough consumption in participants to be linked to cardiometabolic disease (9).

Not Considering Endogenous Erythritol Production

Looking at the studies I discussed in the earlier section, it seems that insulin resistance and high blood sugar levels combined with a diet heavy in glucose and fructose may lead to an increase in serum erythritol levels. High levels of serum erythritol in the blood may be a sign of an unhealthy, inflammatory diet and metabolic dysfunction.

Since the study didn’t look at the erythritol intake of participants, only their blood erythritol levels, it’s very likely that dietary erythritol wasn’t the reason behind high blood erythritol levels and potentially related cardiometabolic issues (2).

However, it’s also important to note that the study in Nature Medicine referenced one small experiment with 8 human subjects who were given 30 grams of erythritol for a 7-day period. They observed a significant increase in their serum erythritol levels.

However, in that experimental study, they didn’t measure markers of blood clotting or other cardiovascular markers, so we don’t know if this increase due to dietary erythritol had any effects or not. It was also a small sample with 8 participants, too small to draw conclusions (2).

From research, we know that high serum erythritol levels are associated with a higher risk of heart attack and related death. We also know that eating erythritol can increase serum erythritol levels.

However, we don’t actually know if consuming erythritol may increase the risk of cardiac events and death or not. Making assumptions is not sound in research because correlation does not equal causation. I will discuss the problem of confusing correlation with causation in a second.

Correlation vs Causation

One of the biggest problems with misinterpreting research studies is confusing correlation with causation. This study found a correlation between serum erythritol levels and heart disease, not causation. Correlation is not causation.

Let’s refresh our memory from high school science class, and let’s go over the difference between correlation and causation. Correlation refers to a statistical relationship between two variables. When two variables are correlated, they tend to change in a similar direction.

A classic example of this shortcoming is the correlation between ice cream sales and violent crimes. As you can see on the graph below the correlation between ice cream sales and violent crimes is very high. Does that mean that ice cream causes violence?

The more accurate conclusion may be that during the summer months when the temperature is elevated (and ice cream sales are coincidentally higher) violent behavior is more prevalent. Coincidentally, research has also shown that hotter temperatures consistently correlate with an increase in violent crimes.

Jumping to Quick Conclusions Make Great Headlines

Causation refers to a relationship between two variables where there is a direct relationship and one variable directly causes the other variable to change. Causation is not based on assumptions but on scientific and statistical evidence on the cause-and-effect relationship showing that one variable can directly change the other variable. For example, based on research, we know that smoking cigarettes may increase the risk of lung cancer.

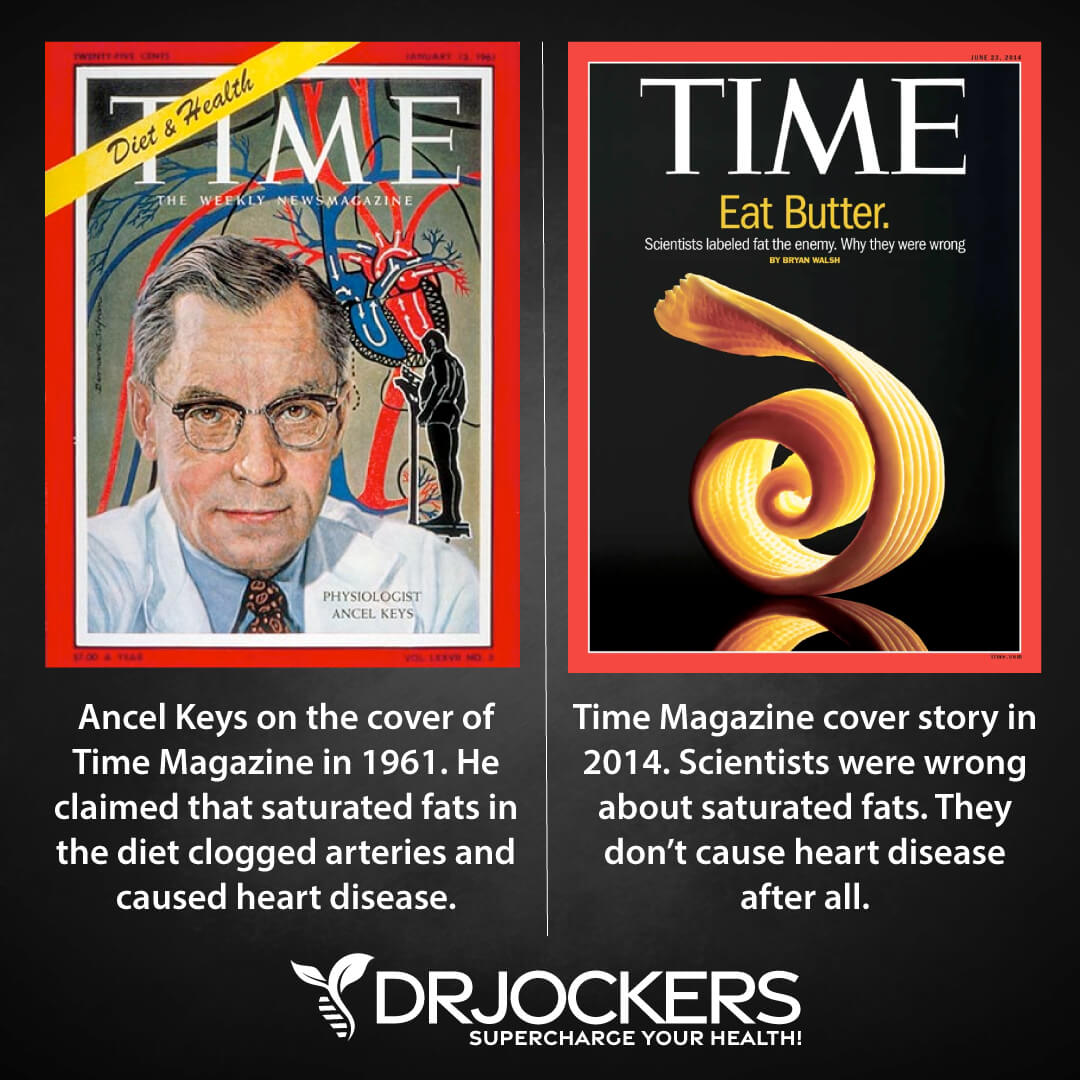

Correlation doesn’t necessarily imply causation, yet, when it comes to this specific study, news reports assume causation. This happens more often than you think. For example, research has shown that saturated fat may increase serum cholesterol levels, and high serum cholesterol may be linked to an increased risk of heart attacks.

Therefore, even the scientific and medical community assumed causation, declaring that eating saturated fat may increase the risk of a heart attack. Yet, recent evidence suggests that eating saturated fats doesn’t seem to increase the risk of heart attacks, and saturated fats and cholesterol may actually offer health benefits. You can learn more about this here.

A similar mistake was seemingly made with this recent study assuming that erythritol may directly cause heart attacks and other cardiovascular events. But as we discussed in the earlier sections, it’s highly likely that a poor diet high in glucose and fructose was driving serum erythritol levels, increasing the risk of cardiac events.

Now, it’s possible that erythritol intake may also play a role in heart issues. But we simply don’t have any evidence of this looking at this or other studies on erythritol. Some others suggest that the opposite may be true though.

A 1996 animal study published in Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology has found no changes in body weight or adverse changes in metabolic and other biomarkers in rates after consuming a diet of 10 percent made up of erythritol after two years (10).

According to a 2021 animal study published in the Journal of Nutrition, the plasma erythritol levels of mice increased by 20 to 60 fold after 8 weeks on an erythritol-rich diet compared to the control group (11). However, they didn’t find any difference in glucose intolerance, body weight, or adiposity. These are only animal studies, and we need more research to fully understand the possible effects (positive or negative) of erythritol.

Additional Erythritol Studies

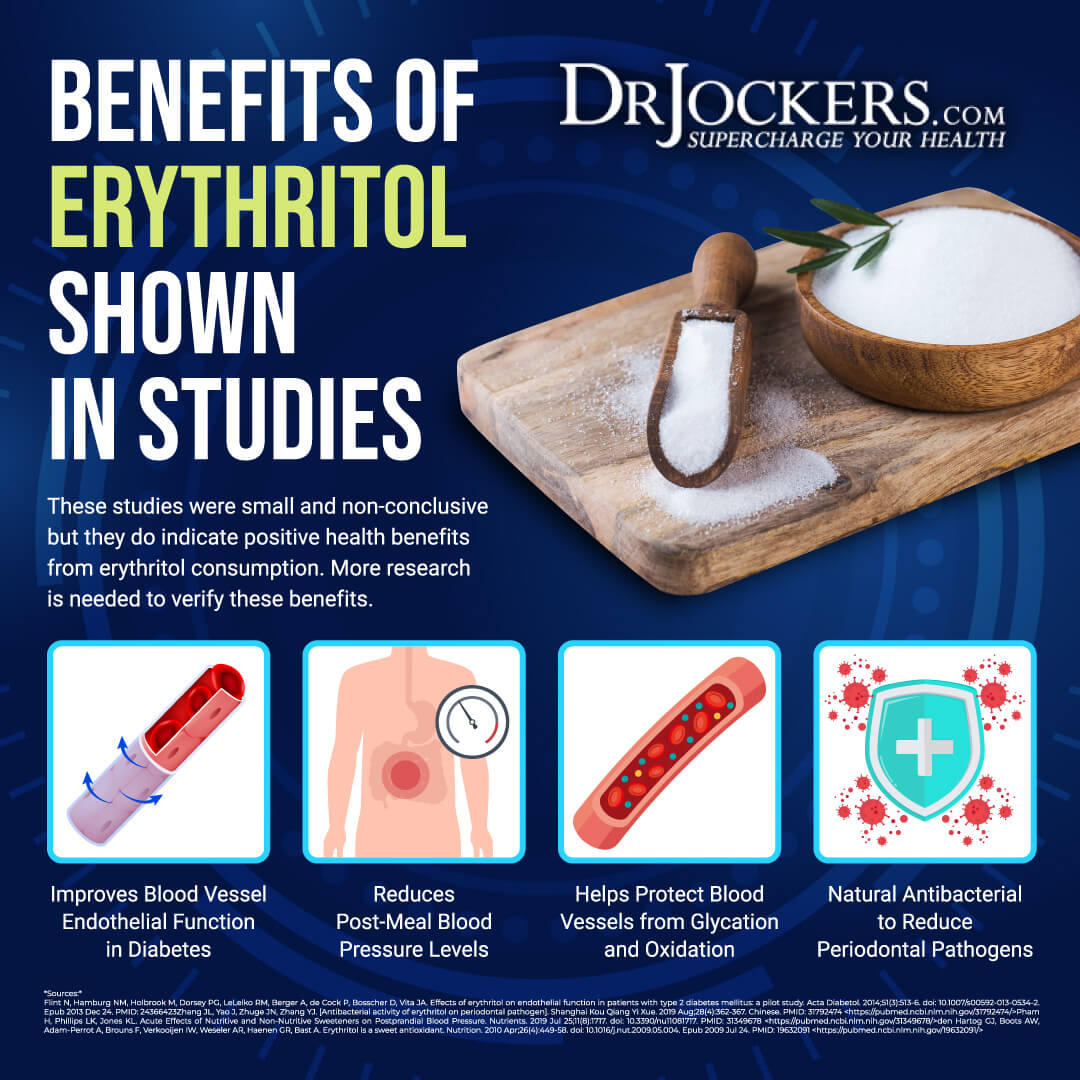

There are some additional studies that suggest that erythritol may have some health benefits. A 2014 pilot study published in Acta Diabetologica has found that erythritol may help to improve endothelial function in type 2 diabetes patients (12). A 2019 study published in Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue has found that erythritol may help have antibacterial effects on periodontal pathogens (13).

A 2019 study published in Nutrients has found that consuming erythritol instead of glucose and fructose may help to reduce post-meal blood pressure (14). According to a 2009 study published in Nutrition, erythritol may be a source of antioxidants that may help to protect blood vessels from diabetes-related damage (15).

As you see, there are some studies that suggest that erythritol may be good for your health and has no negative impact. However, we need more research to have a full picture. It would be wise to do more research here to discover the pros and cons of this sweetener and sugar alcohols in general.

Main Side Effects of Erythritol

Erythritol may be a helpful low-calorie, no-sugar/low-sugar sweetener, but it may not be tolerated well by everyone. Digestive symptoms, including gas, bloating, cramps, and diarrhea, are the main side effects of sugar alcohols that may affect a certain subset of the population.

It may still be a better option than other sugar alcohol sweeteners. According to a 2007 study published in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, people who took erythritol experienced significantly fewer digestive issues than those using xylitol (16).

If you want to use erythritol, I recommend trying it out and small quantities. Starting small and slow will help you see how you feel. If you feel okay using it in small quantities, you can start gradually increasing the dosage until you find a comfortable tolerance point.

If you find that you are intolerant and experiencing symptoms at a certain point, back off. If you find that you are intolerant to even a little bit of erythritol, stop using it.

Final Thoughts

This recent study on erythritol has brought up a lot of confusion and misconception about this natural sugar substitute. Erythritol has been shown to be synthesized endogenously from glucose via the pentose-phosphate pathway (PPP).

Thus, endogenous production of erythritol from glucose may contribute to the association between erythritol and obesity observed in this study. Other studies have shown that the sweetener improves endothelial function and have shown that it reduces a cardiovascular disease-promoting periodontal pathogen.

The takeaway from the study is that the individuals who were obese were endogenously producing erythritol and that they were metabolically damaged and inflamed, and that is the reason for the increased risk of blood clotting and heart attacks and not the consumption of the sweetener.

With that said it would be nice to see more studies on erythritol and other sugar alcohols in the future. But we certainly cannot make the accusation that the study authors and media made with this. If you are interested in using this sweetener or sugar alcohols in general, follow my guidance at the end of the article and listen to your body. Let’s stay on the lookout for future studies.

If you want to work with a functional health coach, I recommend this article with tips on how to find a great coach. We do offer long-distance functional health coaching programs. For further support with your health goals, just reach out and our fantastic coaches are here to support your journey.

Inflammation Crushing Ebundle

The Inflammation Crushing Ebundle is designed to help you improve your brain, liver, immune system and discover the healing strategies, foods and recipes to burn fat, reduce inflammation and Thrive in Life!

As a doctor of natural medicine, I have spent the past 20 years studying the best healing strategies and worked with hundreds of coaching clients, helping them overcome chronic health conditions and optimize their overall health.

In our Inflammation Crushing Ebundle, I have put together my very best strategies to reduce inflammation and optimize your healing potential. Take a look at what you will get inside these valuable guides below!